There is good silence, like the beat of rest in a well-executed call, and there is bad silence. Bad silence not only vacuums coxing from your brain, it erases the entire English language. Rowers know the difference between beats of rest that allow them to focus and that silence that leaves them stranded and alone, without their eyes or ears.

Bad silence is deafening. It is quicksand. You try to fight it, but the harder you fight the deeper you sink. Every coxswain has experienced this, and through the length of a season, or in my case the totality of a career, it will happen so many times you will lose count. This bad silence should not be confused with talking less which is an important skill. No, the bad silence is when you have nothing to say, or worse, you forget what to say. It creeps into your brain through cracks in your focus and holes in your preparation and fills your lungs like cement. You can’t think, your mouth hangs open, and you become a passenger in the worst possible way.

Coxing is like bouncing a ball: the action or throw is rowing; the reaction or bounce is coxing. Sometimes you forget the ball is coming your way. Sometimes the ball hits you in the face. That “hit in the face” is bad silence. Though the ball may hit you most frequently when you are complacent or letting your mind wander instead of focusing, it hits the hardest when you are afraid. Fear fuels bad silence. It is coxswain kryptonite.

If coxing juniors is compared to a lion tamer cracking a whip and yelling, then coxing the national team is like being an old sheep dog gently guiding the herd in the direction they are already going, occasionally nipping at a straggler.

When I first got to the Princeton Training Center, I wasn’t permitted a CoxBox for over a month. Coach Teti said I didn’t need a Box because nothing I had to say was important, and he was right. The reality was I had to focus on significantly improving my steering. It was a very hard month, and I spent most of it thinking I would be sucked under Mike’s stillwater (launch). Mike’s “improving my steering” instruction consisted of him driving right up to the eight so that my stern was under his deck and his pontoons were surrounding me. This is one heck of a way to learn, but it worked. Once I was given a Box, I was terrified of over speaking, or worse, annoyingly repeating myself. The result? I was enveloped by the bad silence.

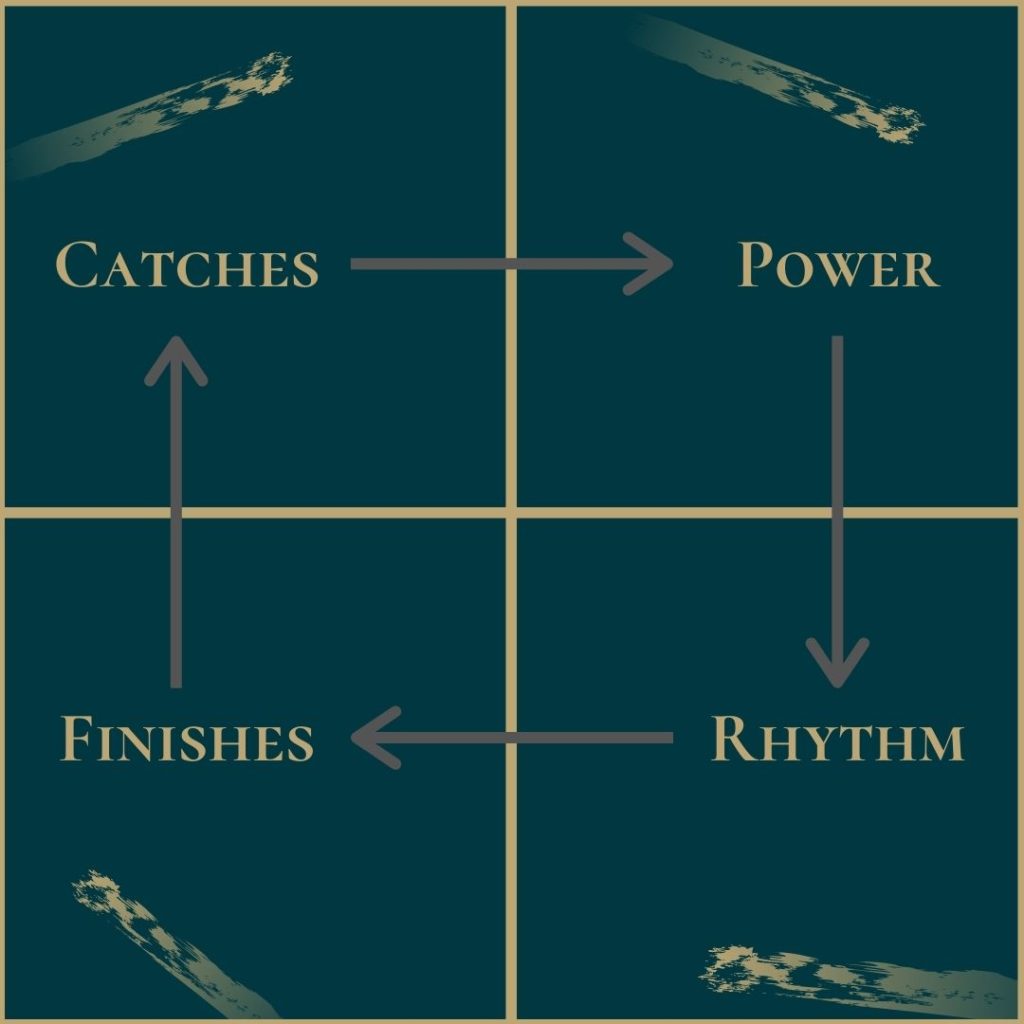

A few months earlier at The Training Center I had had an awful experience in a coxed four, which had ended with me getting annihilated as a “Stupid f**king idiot!!” by two members of that crew. I was so nervous in that four, that I didn’t know what to say…so everything I said was drivel. Determined not to let this happen again, especially because one of the rowers from the summer four was in the eight, I came up with a plan before practice one day. The plan was Coxing in a Square to hone my focus, one element of the stroke at a time. I broke down calls into four types: Catches, Power, Rhythm, and Finishes. These four types do not include boatmanship, transitions or other changes and are meant to cover nearly all in-motion and technical calls. I realized that by focusing on those four parts, one at a time and in order for 10 or 20 strokes, I would never get lost because I always knew the “next” place to go. More on the order and getting “lost” later, but what I had done in that moment was create a roadmap that naturally organized incoming information.

In other articles I have referenced and explained all the incoming information a coxswain must process. Learning to process the sounds, sensations or signals bombarding your senses takes time and for a junior cox it can be like trying to untie a gordian knot. The process of sensing something in the boat, identifying what it is, then developing and executing a call can feel like it takes forever. The pressure of doing all that while steering and managing boatmanship during practice or a race IS daunting. This is why the most common question Junior coxswains ask me is “What do I say?” What I was experiencing at the training center was not the overwhelming “what do I say” chaos of processing too much information in a Junior boat. It was the exact opposite. I had never been in such good boats before, and the information I was getting left me lost and doubting my capacity to contribute. Also, Mike-freaking-Teti was in the launch next to us!

This is the sensation you’re almost certain to feel when transitioning from Junior to collegiate rowing which is why you should learn the square.

Catches, Power, Rhythm, and Finishes in that order make up the four parts as shown in the graphic below:

Take some time and write every synonym you can think of for each of the four elements. Note that each synonym does not need to be just a word or a call. They can be whole thoughts. Here are a few examples:

Catches:

- Lock on

- No miss

- Backsplash

- Placement

Power:

- Speed

- Hang on it

- Bend

- Legs Down

Finishes:

- Send

- Clean

- Dark Water

- Down and away

Rhythm:

- As one

- Matching

- Swing

- Tempo

The lists for each element are endless to the point that you can cox with the square for an entire day and probably never repeat yourself. If you go through the synonyms and include other relevant information like rowers’ names, or reiterate key words from the coach (during practice), any redundancies or repetition will be de-minimis. It will also help you focus by providing a next thought, and because it can be started at any point in the sequence, you’ll never get lost. The square not only gives the coxswain balance in their calls but helps them guide rowers through the typical pitfalls of focusing too hard or too long on one specific thing. We all have limited bandwidth, so as coxswains it is important to be conscious of where we are directing the rowers’ focus and what the primary and secondary impacts of that direction will be.

The sequence can start anyplace as long as the order is not changed. For this explanation, I will start at the catch. Asking rowers to focus on catching better will scrub off some of the explosiveness, and by default power, from the first six inches of the stroke. This is because they’re trying not to miss water which results in a slightly heavier feeling through the drive. Obviously you don’t want this heavier feeling to stick around and for the speed to sag, so focusing on power, like “fast legs!”, is next. Once a crew ramps up their power, they are accelerating through the stroke faster which can only be maximized with a slightly longer recovery, allowing the boat to run out more. This natural evolution between the changing timing of the drive and recovery necessitates the rhythm calls. Typically, when focusing on rhythm rowers become focused on matching their bodies and moving down-and-away together. This results in the softening of the finish, or a row-out of the blade, which will require your attention and make finishes last in the sequence. Then you’ll be ready to start again at catches.

All levels of rowing require coxswains to be flexible, with the ability to hop into any boat and do their job. Growing within a junior program will lead to coxing faster crews, as will coxing in college and beyond if that is what you choose. The role of the coxswain does not allow time to get to know each other, and provides very little room for error. Like a teacher who announces at the beginning of a semester “The way I grade is that you all start with 100 and I subtract points…”, a coxswain is the leader from the moment he or she is introduced to a crew, and needs to be prepared to squash the fear, ward off the bad silence, and cox. That being said, it is important to understand where The Square fits in with the lessons, “Saying Less and Meaning More,” “The F Word,” and “The Rower Whisperer.”

This is not an assurance that if you start endlessly talking in the boat, you’ll be okay as long as you follow my sequence. The square is, first and foremost, a filter. It is meant to act as a ground floor coxswains can build on. I have never sat in the boat and thought “Dan, now say something about power” or “Jeez I need to talk about catches” and neither should you. The square is a safety net that allows you to be in the moment and to find the right call for your crew. Mastering it is the realization that the square is is not telling you what to say, but guiding you where to focus.