Our coach loved 15-minute pieces in a 5,4,3,2,1 structure starting at an 18 rating – we did them all the time – and I was in for another day of losing in even boats.

It was late September, 2004 and I was getting beat by the new guy. As my third year of college rowing began, my rowers were suddenly enamored with the shiny new freshman recruit. I got it. The team had been hearing my voice for two full years; I was old hat. This wasn’t the first time I had to weather my teammates favoring a new and different cox, but it was the first time it had happened to me in college and the first time that the other guy was really good!

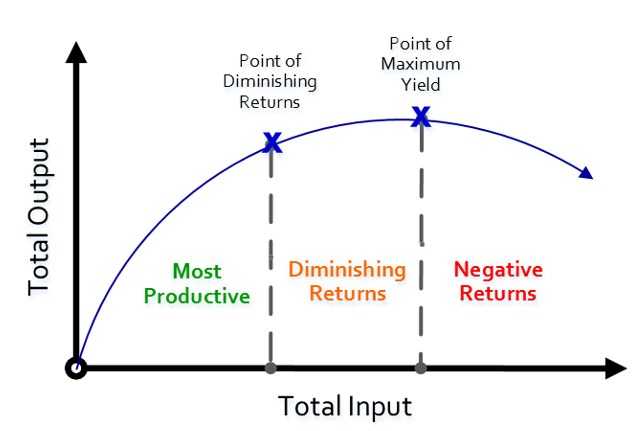

The frustration of hearing a sharp new coxswain, relaxed yet aggressive, beating my crews up one side and down the other was starting to boil. I didn’t know what to do. Coxing my crew, I struggled to listen to this new coxswain, trying to figure out what he was doing, how he was doing it . As I reached to turn up the volume on my box, the law of diminishing returns suddenly dawned on me.

Though this was early season steady state, these boats were not moving slowly. The Freshman was coxing like it was late Spring and I knew from experience that he could never be aggressive enough to get more out of his boat.

I turned up my cox box prepared to match his fire but instead moved the microphone closer to my face and began to whisper. Literally, whisper.

“Breath boys. Relax”

“I need more speed” “Relax n’ get ready to move”

“Ten. Break the blade”

“1”

“2”

“3. Shhhh”

With sixteen blades driving through the water, coach red faced screaming, and the new coxswain trying to stoke the fire he had built, my whisper sent a shock wave through the crew. The contrast from what the rowers had been hearing for the last hour was so jolting it created a level of focus I had never seen in an early season line-up. I had their attention. Now I simply did my job and gave them the information they needed to succeed. They needed to relax, they needed big hanging drives, and they had the speed to win. By the end of practice the new shiny freshman had lost his luster, and was never ahead of me again – ever!

Imagine you’re trying to make a massive bonfire . You want it to burn long and hot, so you add more and more wood. The laws of Physics teach you that eventually the fire will be so big that the wood you are adding won’t contribute to the intensity of the fire but will merely feed the flame at its current level. This is the point of Maximum Yield.

The realization and subsequent decision to whisper to my crew that day wasn’t just about me beating one coxswain, one time. It was about me learning to communicate better, and to “read the room” as a DJ would say. I didn’t invent something new, I learned something new. Ferocious barking has no place in steady state, but I didn’t know that (at the time). My crews weren’t getting beaten because of some shiny new recruit. They were being poorly led by me. Yes, the other boat was mainlining uncut coxswain fire, but I had been holding my crew back more than he had been pushing his forward. The revelation gave way to years of practicing and tinkering with whispering, as well as subliminal sounds or syllables with the goal of conveying as much information to my crew as efficiently as possible.

Whispering, which can sound more like a growl or simply speaking quietly, is a powerful tool every coxswain should master. First, it forces a base level of attention and focus within the boat that a louder cox will not command. By being a little quieter, in a sense, you’re making the rowers come to you, forcing them to pay attention and process the calls. Second, you are leaving yourself space to work. If the last 500 of a 2k is a level 10 of intensity, pushing off the dock and warming up at 7 doesn’t leave you much to work with, and dulls the effectiveness of that level 10 fire. Finally, and most importantly, whispering lets you set the tone. For the practice, for the race, for the week, your quiet intensity will guide them to the fight.

Coxswains talk a lot. On the water, off the water, in meetings, in the weight room, in class…….you get the point, and it is very easy for rowers to accidentally tune us out. Yes, many tune us out on purpose, but that’s a whole different topic. Because the position has you talking so much, it is important to be mindful of your tone. Work to differentiate between your land calls and your water calls or “coxing voice.” This can be difficult, but it is definitely something that deserves attention. Here is a simple example why. Imagine you’re on land standing close to the coach and are asked to tell the captain along with the three girls she is standing with to help the novice roll their shell into slings. The girls are 50 feet away, and you could easily yell or do what every other cox does, which is yell while walking toward them. Instead, stop and think. What was the level of the coach’s urgency? Can you walk, or jog over to them and convey the message by talking, instead of yelling? Always avoid yelling when you can. The rowers will appreciate it, and your calls on the water will be that much more impactful.

“Subliminal sounds or syllables” is my definition of making noises that aren’t words. Chances are you are already doing this, and if you aren’t you’ve definitely heard a recording of another coxswain doing it. These sounds include the ever popular “Cet’” and “ Jhaa” which coxswains call at the catch and finish respectively. If you don’t know what these sounds or syllables are, below is a very basic example:

“Sitting up, let’s take 10 for finishes”

“On This one.”

“1……Jhaaaa (said at release or send), 2….Jaaaa……..” and so on and so on

You’re using “Jhaa” to mimic the sound eight oarlocks make at a good matched release. Like “Cet’” is a shortened version of the word catch that you can use to create the little splash catch sound on the front of the stroke. Olympic coxswain, and Stanford Coach Yaz Farooq calls this “Rhythm Speak,” and I do not think there is a better name for it. Rhythm Speak is the use of sounds to model the rhythm of the crew as shown in the example above. Popularized by the 1997 Pete Cipollone Head of The Charles recording, this is a powerful tool to bring, and keep, crews together through a piece. Simply put, you are using sounds to convey physical motions or feelings.

If you’re already Chaaaing and Jhaaaing, as they say, that is okay and if you aren’t that is okay too. Like any other part of coxing (excluding safety), there is no one or right way to do it, and this skill should be “personally” developed along with your other coxing skills. I remember when I first coxed like this. I had heard Pete’s recording for the first time my Senior Fall in high school. The boat ate it up, and just like that day in college when I decided to whisper, the boat flew. My use of “Rhthym Speak”, along with whispering, has been evolving and comes in and out of my rotation as necessary.

There are only three steps to executing a call that includes an additional or augmented syllable or sound. First, know what you are trying to convey, and if you are going to substitute a whole word for a single sound; like “Jhaaa” for “Send.” These noises should not be random. Second, know the sound you’re going to make and have a clear understanding of the inflection and how it embodies what you’re trying to convey. Third, land the call! You have to place the sound exactly onto the feeling the rowers are experiencing in real time. Late or early, makes the call useless and distracting. Example: If you want to say “Jhaa” at the finish to help the crew subconsciously match the release but say it on the recovery, a rower will think, what the heck is that?! The goal here is for them not to think. Just to hear it, process it, and improve.

A good way to start using or improve the use of these sounds in your coxing is to think of them within the coxing square. If you are moving through the bottom half or the square, and making calls to help the crew focus on their rhythm you add “Jhaaa” to some of the finishes as you transition to that part of the square. This is a simple way to create continuity, connecting calls and keeping the rowers attention. Below is a basic example:

“Good rhythm, swinging tall.”

“Tall (said during drive), swing (said through finish and send)”

“Nice”

“Tall (said during drive), swing (said through finish and send)”

*One silent stroke*

“Tall (said during drive), swing (said through finish and send)”

“Good. Move as one. Powerful rhythm.”

“Move (said after first 6inches of drive), Rhythm (said at finish)”

“Move (said after first 6inches of drive), Rhythm (said at finish)”

*One or two silent strokes*

“Nice”

“Move (said after first 6inches of drive), Jhaaa (said at finish)”

“Move (said after first 6inches of drive), Jhaaa (said at finish)”

In that example “Jahh” is being used to mean matching, finishing, rhythm, all at the same time. You can change the inflection depending on the pace of the row or any other factor (like head wind or current) and you have given yourself a path into your next call.

Augmenting syllables with sounds is far more common and requires strict adherence to the same three steps listed in the above paragraph. Simply: You take a word and extend, or emphasize one syllable. Adding extra L’s to the word tall when you want a crew to sit up, or extra E’s to the word breath when you want them to relax. You are using your voice and changing words to convey what you need the rowers to feel. For example, a lot of coxswains say “Breathe” when they want a crew to relax, especially after a rating shift. I use a step of three breathes all getting longer in length and lower in tone. “BreEaTHe” is said with a sharp E (gets their attention) “BREthaee” (help them relax) “BReeeeaaathhheeeeeeeee” (helps them settle in to where they need to be).

If you listen to the 1997 Pete Cipollone recording, which I am sure you have by now, take note of the long S’s on send, and the exaggerated E’s in legs. He’s not just saying the word “Legs”. He is conveying strength,power, and ferocity. One of the most effective calls I’ve ever used is made specifically after the high portion of a start, once the crew has shifted to race rate. It is simply “speed relax.” I know on the surface is not an impressive or creative call, and the two words aren’t even that special. The power and effectiveness of the call relies completely on the delivery. The word “speed” is crunched into a sharp jolt with a long S, extra E’s which climb in both pitch and volume and a soft D. It sounds like the word is racing the rowers through the drive pushing them towards the bow. The word “relax” is drawn out into a dull slack pile of letters with an R hard enough to get the crew’s attention, but bland enough to juxtapose the previous word. The E, A, and X all get drawn out depending on how well the crew is responding. If a crew settles too high, it’s better to lull a crew down a beat and relax them into race pace than to notify them and make a specific call that could throw off the rhythm. The long E, A and X are very useful at helping a crew find their race pace. After the rhythm is locked in I use a curt “good” to let them know, then continue through the race plan at an intensity just above the “relax”, leaving me plenty of room to stoke the fire.

We know that this lesson only scratches the surface of two very complex topics, and it is with that knowledge that I will reiterate the mission statement of Rower Academy for Coxswains. Our goal is not only to help you grow, but, more importantly, to guide you to ask the right questions.

Don’t ever lose sight of that fact that rowers are trying to do their job too, and the crew will function best when everyone does their jobs in harmony. An important part of a coxswain’s job is to maintain an awareness of the crew’s threshold of information retention and processing. This awareness should be maintained not just piece by piece but through each practice as a whole. Whispering, and using sounds, or augmented syllables in place of words are great tools that will help you cut down on excess chatter, and deliver your boat exactly what it needs to know.